Ellen Ochoa was rejected by NASA three times before the agency realized it had misunderstood what it was looking at. She was not failing the process. The process was filtering out the wrong kind of excellence.

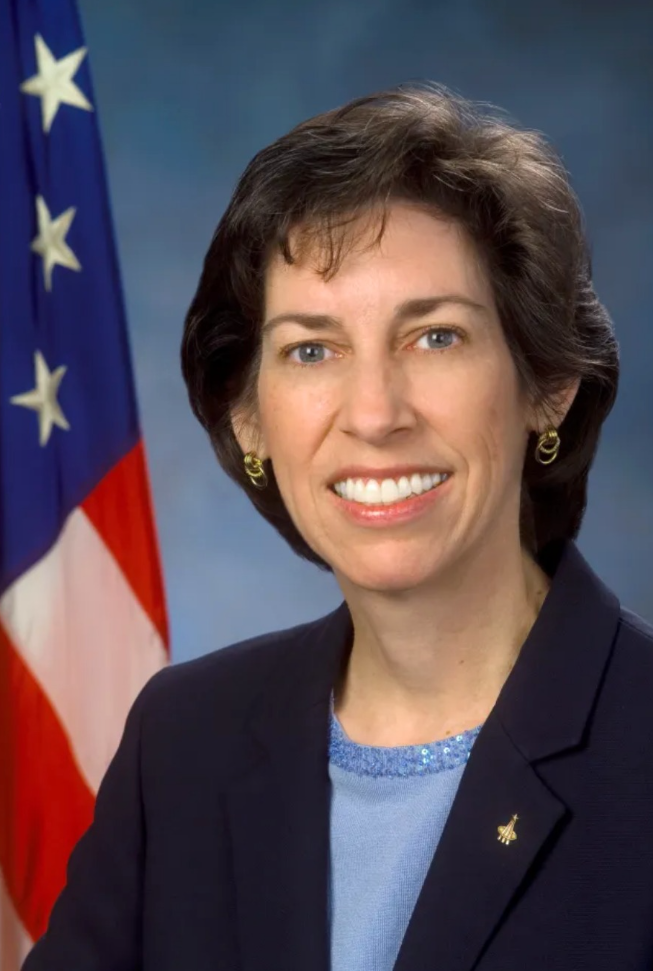

In the early 1980s, NASA’s astronaut corps still ran on a narrow template. Military test pilots. Loud confidence. Command presence that filled rooms. Ellen Ochoa did not fit it. She was a civilian scientist. Soft spoken. Methodical. A specialist in optical systems who spent her days writing code and calibrating instruments that had to work perfectly or not at all.

NASA turned her down in 1983, 1984, and 1985.

What the rejection letters did not say was that Ochoa already held multiple patents in optical information processing, technology that would later be used in image correction and robotic vision. She was solving problems astronauts would eventually depend on, while being told she did not look like one.

She applied again anyway.

In 1990, NASA selected Ellen Ochoa as an astronaut candidate. Two years later, in April 1993, she flew aboard STS-56 Discovery, becoming the first Hispanic woman in space. She was not there as a symbol. She was there because her systems expertise mattered. During that mission and three more that followed, Ochoa worked on robotic arms, satellite deployments, and experimental payloads where precision was non negotiable.

She flew four space shuttle missions between 1993 and 2002, logging nearly 1,000 hours in orbit. She did not chase headlines. She did not cultivate myth. Inside NASA, she gained a reputation for something quieter and more dangerous. Reliability.

That reputation carried weight later.

In 2013, Ellen Ochoa became the first Hispanic director of NASA’s Johnson Space Center, the nerve center of U.S. human spaceflight. She now oversaw thousands of employees, billions of dollars in infrastructure, and missions that defined national prestige. The same institution that once rejected her three times now trusted her with its core.

Ochoa used that authority deliberately. She expanded pathways for scientists, engineers, and non military candidates. She pushed back against the idea that astronauts had to perform bravado to belong. Competence became the standard again.

Ellen Ochoa did not break into NASA by being exceptional once.

She broke it open by outlasting a system that confused loudness with readiness and familiarity with merit. When NASA finally adjusted its vision, it discovered it had been orbiting her work for years.