The winter did not arrive in the Montana Territory the way polite winters did back East, with a few graceful flurries and a picturesque dusting for postcards. It arrived like an uninvited debt collector, boots on the porch boards, knuckles on the door, not leaving until it took something.

Juniper Ridge sat in a valley where the pines leaned under the weight of snow and the mountains watched with the patient cruelty of stone. Three feet of white had buried the road markers, muffled the creek, and turned the town into a quiet little lie that looked peaceful until you listened closely and heard what quiet really was: hunger held in, resentment held in, grief held in, and on certain nights, the soft sound of people deciding what they would do to survive.

Inside the town hall, warmth made its own kind of fog. Kerosene lamps glowed yellow against timber walls. The air smelled of roasted ham and cider and wet wool steaming on shoulders. There was laughter too, plenty of it, but laughter in Juniper Ridge could be a weapon as sharp as any blade if you weren’t the one holding it.

The Christmas box social was the biggest event of the year. That was the name, anyway, because “auctioning women’s baskets to men who wanted an afternoon of company” sounded too honest for church folk. The premise was simple enough to be defended as wholesome: the ladies prepared a lunch for two and wrapped it in ribbons and secrecy; the men bid; the highest bidder won both the meal and the privilege of the lady’s company for the afternoon. The money, they said, went to repairs for the church roof.

Clara Whitlock stood near the back of the stage and smoothed her hands down the front of her dress for the tenth time, as if the gesture could iron out the year that had happened to her.

Her calico was a tired gray, faded at the seams, respectable only because it was clean. It had been her best when she married Samuel Whitlock, and now it was her best because everything else worth anything had been traded away in small, humiliating increments. A quilt for flour. A skillet for lamp oil. A silver hairpin for a sack of feed. In towns like Juniper Ridge, poverty wasn’t simply lacking money. Poverty was being watched while you lacked it.

Behind her, the curtain was nothing more than heavy cloth hung from a beam, but it couldn’t hide the murmur rolling through the room.

“Look at her,” someone whispered, a woman’s voice sharpened to a needle. “Gray to a Christmas social.”

“You’d think she’d have the decency to stay home,” another replied, dripping sympathy like syrup over poison.

“She can’t afford to stay home,” came the answer. “I heard First Ridge Bank is coming for the Whitlock place come spring. She’s trying to catch herself a husband before the note comes due.”

Clara kept her chin high, because lowering it would have been an admission, and admissions were a kind of surrender. Her hands, though, betrayed her. They trembled slightly around the handle of the basket she held, and the wicker bit into her palm.

The basket wasn’t just lunch. It was her last lever, the final tool she could press into the machinery of Juniper Ridge and pray it moved in her favor. Inside, she had packed the last of her winter stores like offerings laid on an altar. A jar of preserved pears from two summers ago. Biscuits made from the last scrape of flour. A small meat pie—venison—earned by trading her wedding ring’s silver polish to a hunter with soft eyes and a hard season.

It was meager. It was honest. It was all she had left that still felt like something a decent woman might give without begging.

At the front of the hall, the auctioneer—Amos Pritchard, broad as a barrel and sweating despite the cold—banged his gavel for quiet. He’d been jovial a moment earlier, praising the mayor’s daughter’s basket like it was a banquet in miniature. But when his gaze slid to Clara, his expression tightened, as if he’d tasted something sour and couldn’t pretend otherwise.

“All right now,” Amos called, voice loud enough to sound confident. “Next up we’ve got a basket wrapped in… well, it looks like sturdy red flannel.”

A few chuckles. A few coughs. A few men suddenly fascinated by their boots.

Clara stepped forward.

The chatter died instantly, but it wasn’t the respectful hush of anticipation. It was the cold vacuum of exclusion, the kind of silence that says, we have agreed, without speaking, that you do not belong.

“A fine basket by Mrs. Clara Whitlock,” Amos announced, though he didn’t bother to add any flourish to her name. “Do I hear fifty cents?”

Nothing.

Outside, wind pressed its face to the windows and howled, and the sound only made the stillness inside feel more deliberate.

“Come now,” Amos tried again, shifting his weight. “Surely someone’s hungry. A quarter. Twenty-five cents for a home-cooked meal.”

Clara felt heat rise up her neck and stain her cheeks. Not because she was embarrassed to feed someone. She’d fed half the valley at one time or another, back when Samuel’s laugh was in her kitchen and his hands were strong. She burned because she understood the message of their silence. They weren’t refusing her food. They were refusing her.

In the front row, Mayor Silas Crowley sat with his thumbs hooked in his vest, mustache thick as a broom and eyes bright with a satisfaction he didn’t bother to hide. Crowley’s smile was not kind. It was managerial, like a man watching a lever finally break under pressure.

He stared directly at Clara, and she could practically hear what his gaze was saying:

Give up the land, and this ends.

The Whitlock homestead sat on a rocky patch beyond North Fork Creek. It wasn’t good soil; you could coax beans out of it if you prayed hard, and you could keep chickens alive if you watched the hawks. It wasn’t the sort of place a mayor wanted, not unless he wanted something else that lay beneath it. Crowley had offered her pennies for it right after Samuel died, smiling in that same way and calling it charity. Clara had refused. A refusal, in Juniper Ridge, was an insult. A widow’s refusal was rebellion.

“Ten cents?” Amos tried, voice thinning. “A dime for a meal and company.”

A titter of laughter rippled among the women. Not loud, not enough to be openly cruel, just enough to make clear that cruelty didn’t always shout. Sometimes it giggled.

“Going once,” Amos said, lifting the gavel.

Clara’s eyes burned. She would not cry. She would not give them that satisfaction, not here, not under those lamps, not with Crowley’s gaze on her like a hand.

She prepared to turn, to walk off that stage with her basket untouched, and to step back into the snow knowing that tomorrow she would have to decide what dignity was worth when hunger came calling.

“Going twice…”

The gavel began its descent.

And then the double doors at the back of the hall flew open so violently the iron hinges screamed.

A gust of freezing wind rolled through the room like an animal, scattering snow across the floorboards and making the lamp flames flicker. The smell that came with it wasn’t town smoke or cider. It was pine resin, woodsmoke, and raw leather, the scent of the high country.

A shadow filled the doorway.

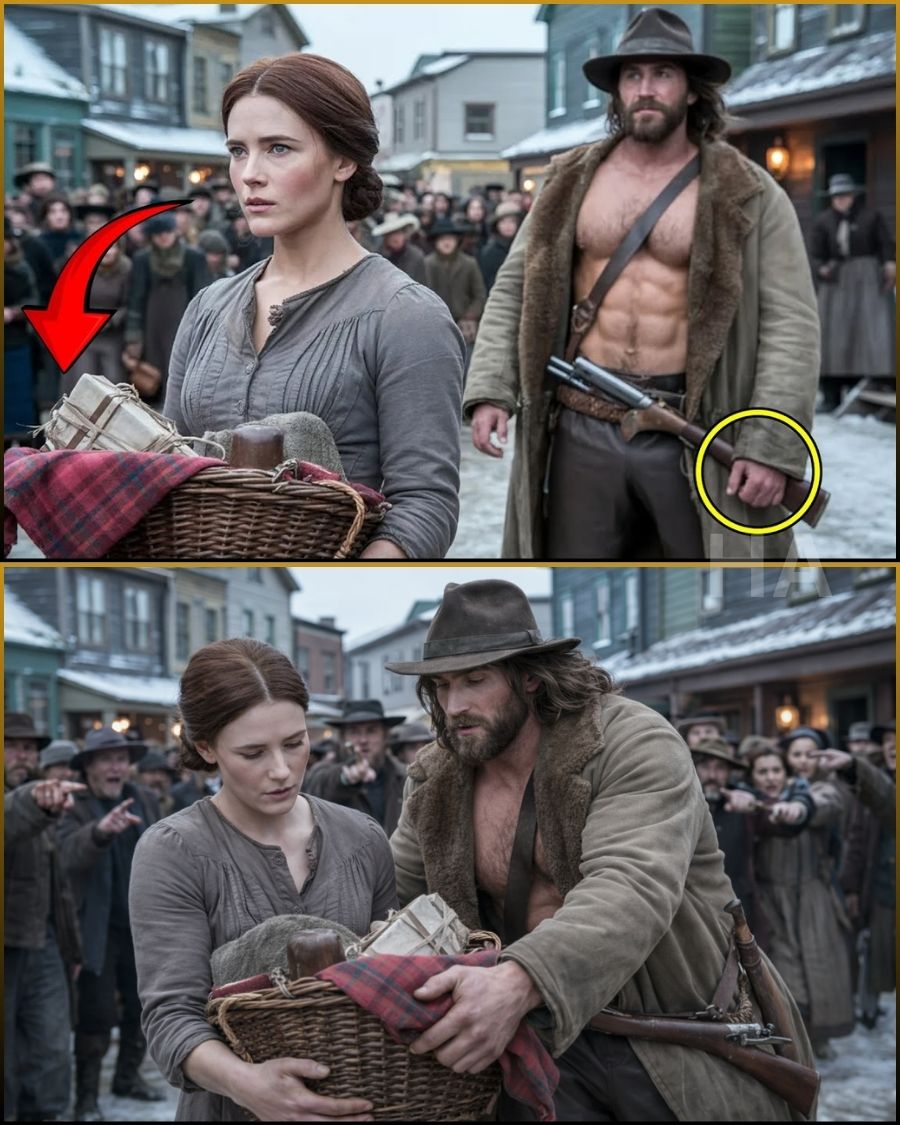

He was massive, easily six and a half feet, wrapped in a buffalo coat that made him look like a creature the mountains had decided to lend the valley for a night. Snow clung to his beard in thick dark tangles. A wide-brimmed hat cast his eyes into shadow, but even from across the room Clara could feel the weight of his gaze, steady and unblinking. A rifle was slung over one shoulder, and a knife sat on his hip, long enough to be unsettling just by existing.

Rowan Kincaid.

The name moved through the hall like a prayer spoken wrong.

Mothers drew children closer. Men shifted their chairs as if distance could be created by will alone. Rowan Kincaid wasn’t part of Juniper Ridge’s polite world. He lived in the Sapphire Mountains, trapping, hunting, and vanishing for months at a time. Rumors stuck to him because people always filled the unknown with stories sharp enough to keep them from feeling afraid of their own ignorance.

They said he’d killed a grizzly with his bare hands. They said he’d been a deserter once, or a bounty hunter, or worse: a man with no loyalty but his own code. They said he had a fortune buried in a cabin. They said he had a graveyard of enemies.

Rowan stomped snow from his boots, the sound echoing. He did not look at the crowd. He did not acknowledge the mayor. His eyes, dark as river stone, locked on the stage.

Locked on Clara.

He walked down the center aisle, and the crowd parted like water around a boulder. No one wanted to brush his coat. No one wanted to be close enough to feel what he might do if provoked. His spurs jingled with each step, a lonely, dangerous sound.

He stopped ten feet from the stage and looked up at Amos Pritchard, who was trembling hard enough that the gavel seemed too heavy for his hand.

“Is the lady’s basket for sale?” Rowan’s voice was low, the sound of distant thunder rolling through timber.

Amos swallowed. “Y-yes, Mr. Kincaid. It is. The bidding is… open.”

“Nobody bid,” Mayor Crowley barked from the front row, rising like a man reclaiming a room. “Auction’s over, Kincaid. You’re interrupting a private community event.”

Rowan turned his head slowly toward Crowley.

He didn’t speak. He didn’t smile. He simply stared.

Something in that stare quieted the mayor in a way Clara had not seen any man quiet Crowley before. Crowley’s cheeks reddened. His jaw worked. But he sat back down, cowed by the obvious truth that Rowan Kincaid did not fear titles.

Rowan turned back to the stage. For a fleeting instant, the hardness in his eyes softened, as if he noticed the fray at Clara’s cuffs, the way her fingers gripped the basket like it was a lifeline, the defiance holding her spine straight.

“Five dollars,” he said.

The room erupted.

“Five dollars!” a woman shrieked, scandalized. “That’s indecent!”

Five dollars was two weeks’ wages for a cowhand. It could buy a good horse or feed a family for a month. It was a price that made the earlier bids of fifty cents look like children tossing pebbles at a mountain.

Amos’s eyes bulged. “I… I have five dollars,” he squeaked, and his gaze darted to Crowley as if hoping the mayor would counterbid out of spite.

But Crowley’s face had gone a shade too purple for holiday cheer. He wasn’t going to spend five dollars on Clara Whitlock. Not when he meant to evict her for free.

“Any other bids?” Amos asked, voice weak.

Rowan reached into his coat. He didn’t pull out a coin purse. He pulled out a small leather pouch, untied it, and upended it into his palm.

Gold.

Not minted coins polished for town, but heavy, honest pieces that caught lamplight and threw it back like a dare. He stepped forward and dropped them on the front table with a clatter that made people flinch, as if the sound itself could bruise.

“Sold,” Amos breathed, and he didn’t even raise the gavel again. It felt like no one in the room owned authority in the same way Rowan owned presence.

Rowan climbed the steps to the stage.

Clara’s heart hammered like a trapped bird. She’d seen Rowan in town before, trading furs for flour, standing in doorways like he didn’t care whether he was welcome. But she’d never been this close. He smelled of cold air, pine, and tobacco, and something else too, something that reminded her of the world beyond people’s opinions.

He stopped in front of her and tipped the brim of his hat, not theatrical, not flirtatious. Just… respectful.

“Ma’am,” he said.

He held out his hand.

It was large, scarred, steady.

Clara looked at Crowley, who was glaring daggers. She looked at the women whispering behind their fans. She looked at the men who had stared at their boots and let her stand alone.

Then she looked at Rowan Kincaid, who was watching her like she was the only real thing in the room.

She shifted the basket to her left arm and placed her hand in his.

His grip was warm enough to be shocking.

“Mr. Kincaid,” she whispered.

“I hope you’ve got an appetite for your own cooking, Mrs. Whitlock,” he said, loud enough for the front row to hear, “because I’d ride through hell and back for a meal that tastes like it came from a home.”

A hush fell, and Clara felt something inside her chest ease, just a fraction, as if her lungs remembered how to take a full breath.

Rowan tucked her hand into the crook of his arm and turned her away from the room.

He led her off the stage.

The widow and the mountain man walked down the aisle together, leaving behind stunned silence and the glitter of gold like a trail of consequences.

Outside, the cold hit Clara’s face hard enough to sting, but she barely felt it. The adrenaline of humiliation interrupted, of dignity unexpectedly defended, was a warmth all its own. Rowan did not lead her to the town square where other pairs sat at tables under lanterns, pretending this was about charity and not possession.

He led her around the side of the hall to a stand of pines, where a black stallion waited, hitched to a rugged cutter built for deep snow. No fancy bells. No ribbons. Just wood, leather, and the promise that it could run if it needed to.

“Up you go,” Rowan said.

Before Clara could protest about the height, his hands settled at her waist and lifted her as if she weighed no more than the basket she carried. The touch was firm, practical, respectful, but it still sent a strange heat through her because it reminded her how long it had been since anyone touched her without taking something.

He climbed in beside her, the cutter dipping under his weight, and threw a buffalo robe over their laps.

“Where are we going?” Clara asked, her voice unsteady now that the hall’s eyes were behind her.

Rowan flicked the reins. “Somewhere folks can’t stare at you while they chew.”

The stallion lunged forward, runners whispering over snow. The town fell away, lights shrinking behind them. They rode in silence for a time, because words took energy and Clara had been spending hers in survival for so long she’d forgotten it could be spent on conversation.

Rowan steered them up a ridge trail that overlooked the valley, to a clearing where the pines thinned and the sky opened wide. Juniper Ridge looked small from there, a scatter of roofs half-buried, smoke curling like tired sighs.

Rowan tied the reins and nodded at the basket. “Let’s see what five dollars bought me.”

Clara’s stomach tightened with shame. Against Rowan’s size, her little offerings seemed smaller still.

He unlatched the lid with careful fingers and began taking things out. The jar of pears. The biscuits. The pie.

Clara blurted, unable to stop herself, “I’m sorry. It isn’t much. The flour was the last of the barrel. The pears are old. It’s poor fare for a man like you.”

Rowan paused with a biscuit in his hand. He looked at the food, then at her, and something in his eyes shifted like ice cracking.

“Clara,” he said, using her first name as if it mattered.

She startled at the sound of it.

“I’ve been up in the high country six months,” he said. “I’ve eaten hardtack that’d break a tooth and jerky tough enough to shoe a mule. This—”

He took a bite of the biscuit. Chewed slowly. Closed his eyes as if savoring not flavor but memory.

“This tastes like a home,” he said, voice quiet and rough. “I haven’t tasted home in a long time.”

He broke the pie in half and handed the larger portion to her.

“I can’t,” Clara protested. “You paid for it.”

“And I’m saying we share it,” Rowan replied, pressing it into her gloved hand. “I don’t eat alone when there’s company.”

They ate there above the town, suspended between cold sky and colder politics, and as the initial awkwardness melted, conversation began to flow. Clara found herself talking, really talking, for the first time since Samuel’s funeral. She told Rowan how Samuel had tried to fix the barn roof even as his heart betrayed him, determined to leave something sturdy behind. She told him about chickens freezing, about repairs she couldn’t afford, about the bank letter that felt heavier than any snowdrift.

Rowan listened without pity, which was its own kind of kindness. Pity always came with the implication that your suffering was your identity. Rowan listened like her suffering was simply weather, something they could plan around.

After a while, Clara’s question rose out of her like a splinter pushed free.

“Why?” she asked. “Why spend five dollars on me? You could’ve had the mayor’s daughter’s basket. I hear she packed roasted pheasant.”

Rowan wiped crumbs from his beard and stared out over the valley. His expression darkened, as if he was stepping into a memory he didn’t like.

“I knew Samuel,” he said.

Clara went still. “You… you did?”

“Two winters back,” Rowan said. “Found him near the pass. Wagon wheel snapped in a drift. He was freezing. I helped him get a fire going. We fixed the wheel. He talked about you the whole night, like you were the reason he could breathe.”

Clara’s throat tightened.

Rowan reached into his coat and pulled out a folded paper, creased from being carried too long.

“He gave me this,” Rowan said, hesitating like a man unused to delivering anything delicate. “Told me if anything happened to him, I should make sure it got to you. I’m not… I’m not a town man. I stayed away. I should’ve brought it sooner.”

Clara unfolded the paper with numb fingers.

It was a crude map of her property, sketched in Samuel’s shaky hand. And on the back, written in charcoal, were three words that made her blood turn to ice and then to fire.

NORTH FORK GOLD.

Clara stared, her heartbeat stalling like a wagon stuck in a rut.

“Gold?” she whispered. “Samuel never… he never said…”

“He found traces,” Rowan said. “Feared if he told anyone, Crowley would find a way to steal the land before he could secure the deed. He wanted to finish paying the bank, then tell you. He died before he could.”

The land. The land Crowley wanted. The land the bank threatened. The rocky soil everyone mocked.

It wasn’t worthless.

It was a mine.

Clara looked up, tears freezing on her lashes. “That’s why Crowley keeps coming. He knows. Somehow he knows.”

Rowan’s jaw tightened. “Then we’ve got trouble. A man like Crowley doesn’t stop because he lost an auction. He escalates.”

The sun dipped behind the peaks, turning the snow violet and bruised. Rowan drove her back to the homestead in silence that felt heavier now, not with loneliness but with implications.

He helped her down from the cutter, his gaze sweeping the property like a hunter reading tracks.

“I should go,” he said. “Ain’t proper for me to linger. Folks talk.”

“Let them,” Clara said, clutching the map hidden in her pocket. “You changed everything today.”

Rowan tipped his hat. “Lock your doors. Hide that paper. Don’t tell a soul.”

Then he rode off, bells fading into the trees.

Clara watched until he disappeared, and the loneliness returned, but it had changed shape. It wasn’t emptiness anymore. It was absence of something that had just begun to exist.

Inside, she lit a kerosene lamp and hid the map inside the hollow of the family Bible, because even fear needed somewhere sacred to sit. She was stoking the fire when heavy pounding shook the front door.

Not a polite knock. A demand.

“Open up, Clara,” a man called. “It’s Mayor Crowley. Sheriff Mercer’s with me.”

Clara’s blood went cold in a way no winter could manage. She grabbed the fire poker and approached the door, forcing her breath steady.

When she opened it, Crowley stood wrapped in fine wool, the sheriff at his shoulder. Wade Mercer was a tall man with tired eyes and a mouth set in a line that suggested he’d chosen survival over pride a long time ago. In Juniper Ridge, the law belonged to whoever signed the checks. Crowley’s hand was always on the pen.

Crowley pushed past Clara without asking, stepping into the parlor like it belonged to him. He sniffed as if poverty had a smell he could judge.

“We need to talk about your situation,” he said, peeling off gloves. “And about that little stunt you pulled with that savage Kincaid.”

“Mr. Kincaid is a gentleman,” Clara snapped before she could stop herself. “Which is more than I can say for some.”

Crowley laughed, dry as old paper. “A gentleman. He’s a drifter, Clara. A violent man. But I’m not here to argue manners. I’m here to make you a final offer.”

He pulled a document from his coat. “Two hundred dollars. Enough to pay your debts and buy a ticket back East.”

“I have no one back East,” Clara said, voice tight. “And the land is worth more than two hundred.”

“Not without a husband to work it,” Crowley said, casual cruelty dressed as practicality. “Look, I’m trying to be charitable, but the bank is calling the note.”

“The note isn’t due until spring,” Clara argued. “Samuel signed it for April.”

Crowley’s smile sharpened. “Ah. That’s where you’re confused. There’s a clause. In the event of the primary earner’s death, the bank reserves the right to accelerate repayment.”

Clara stared, stomach dropping. “You can’t—”

“I own the bank,” Crowley hissed, stepping close enough that Clara could smell brandy on his breath. “I can do what I please. The bank wants its money by noon tomorrow, or we foreclose.”

“Tomorrow?” The word tore out of her like a scream. “That’s—”

“Convenient,” Crowley said, enjoying himself now. “Sell to me tonight for two hundred or lose it all tomorrow for nothing.”

He leaned in, voice dropping. “And don’t think your mountain man can help you. Sheriff Mercer has a warrant for Kincaid’s arrest. Some unpaid debt out in Kansas. If he shows his face here again, he hangs.”

Clara’s grip tightened on the poker until her knuckles ached.

“Get out,” she whispered.

“Noon,” Crowley repeated, putting on his hat. “Don’t be a fool.”

They left, slamming the door so hard the frame shuddered.

Clara sank into the rocking chair, the poker clattering to the floor. Her mind ran numbers like a desperate gambler. She needed five hundred dollars to clear the mortgage. Rowan’s five gold coins might be worth a hundred if she traded well.

Not enough.

She glanced at the Bible where the map hid. If she showed anyone, Crowley would swallow her whole before she could blink. If she did nothing, she’d lose the homestead by noon.

The wind howled outside like mourning, and Clara put her head in her hands and wept. Grief and rage and fear blended into a hot, humiliating storm, and beneath it all, the sharp thought that would not leave her alone:

Samuel died trying to protect this. I can’t let Crowley take it because I’m tired.

A crack snapped through the night. Not wind. Wood.

Clara froze.

She blew out the lamp and crept to the back window, wiping frost away with her sleeve. Moonlight washed the yard pale blue. By the woodpile stood a massive figure in shirtsleeves despite the cold, splitting logs with steady power.

Swing. Crack. Swing. Crack.

Rowan.

He hadn’t left.

He was chopping her wood like a man building a barricade, and Clara felt something inside her chest unclench, because the simple truth of his presence was a kind of answer: she was not alone.

Then she saw movement beyond the fence line. Shadows sliding through trees. Rifles catching moonlight in brief, wicked flashes.

Crowley hadn’t sent a warning. He’d sent men.

Rowan’s back was to them. The wind blew toward the house. He couldn’t hear them.

Clara didn’t think. Thinking took time, and time was what death always asked for.

She grabbed Samuel’s old double-barreled shotgun from above the mantle, threw open the back door, and ran into the snow in her stocking feet, cold biting like teeth.

“Rowan!” she screamed. “Behind you!”

The warning ripped through the night.

Rowan didn’t turn to look. He trusted her voice instinctively. He dropped to his knees as a rifle cracked and a bullet chewed a chunk of wood out of the log where he’d been standing a heartbeat before.

Rowan moved with terrifying speed. He spun, grabbed the axe, and hurled it into the dark. A dull thud. A yelp.

“Get down!” Rowan roared.

Clara did not get down.

She raised the shotgun, braced the stock against her shoulder, and fired. The blast lit the yard orange. Buckshot shredded branches where shadows hid.

“Damn it, she’s armed!” a voice shouted. “Flank him! Get the big one!”

Rowan sprinted through the snow, zigzagging, closing distance like a predator. Clara fumbled to reload, fingers numb, heart pounding so hard she felt it in her throat.

Rowan vaulted the fence and vanished into brush. Sounds erupted. Grunts. The crunch of snow. The sick sound of bone meeting fist.

Then two shapes broke from cover and ran, terror choosing their feet for them.

“Clara!” Rowan’s voice called from the dark. “The cutter! Now!”

She ran to the barn, breath tearing. Rowan emerged, dragging his leg slightly, a dark stain spreading on his thigh.

“You’re hit!” Clara gasped.

“Just a graze,” he lied, voice strained.

“We can’t stay here,” Rowan said, helping her harness the stallion with one hand steadying his wounded leg. “If they don’t kill us tonight, they’ll burn you out by morning.”

Clara looked back at the farmhouse, the only place she’d ever felt safe. “But my home—”

“It’s wood and glass,” Rowan said, snapping the reins. “The home is you. If you want to keep that land, we have to survive the night.”

They launched into the forest, leaving the road because roads belonged to sheriffs and mayors. Behind them, an orange glow rose against the sky.

Clara swallowed a sob.

They had torched her barn.

Crowley wasn’t just stealing land. He was making a point: obedience or ash.

They rode hard for an hour, climbing into the mountains where pines stood like dark witnesses. Finally Rowan slowed near a rocky overhang hidden by spruce, a natural shelter from wind and eyes.

When his boots hit the ground, his leg buckled. He went to one knee with a groan he tried to swallow.

Clara was at his side instantly. “Sit. Let me see.”

Rowan’s jaw worked. “I’m fine.”

“You’re bleeding through your trousers,” Clara said, and the steel in her voice surprised them both. “Sit.”

She lit a small lantern. The wound was ugly, deep, but not fatal. She tore a strip from her petticoat, lace she’d saved for church, and bound his thigh with efficient pressure.

Rowan watched her hands, his face pale in lamplight. “You shoot straight,” he murmured.

“I had to learn,” Clara said, tying the knot. “Samuel couldn’t hold a gun his last year.”

Rowan covered her hand with his, trembling not from pain but from rage. “They won’t get away with this.”

Clara swallowed. “The bank opens at nine. Crowley said noon. Sheriff will be watching the doors.”

Rowan leaned back against rock, eyes closing briefly. “I have the money, Clara.”

She stared. “What?”

“The five dollars wasn’t all I had,” he said, voice low. “I’ve trapped and prospected these mountains fifteen years. I don’t spend it on whiskey or cards. I bury it. I’ve got enough gold dust in my saddlebags to buy your place three times over. But money’s no good if a bullet stops you at the bank door.”

Night passed in cold and whispered plans, their bodies sharing a buffalo robe for warmth while their minds built a bridge from panic to action. Rowan told her about losing his family to fever years ago, about retreating into mountains because grief was quieter among trees. Clara listened and realized the town’s stories about him were lazy, because they never bothered to ask what a man’s silence was protecting.

By dawn, the plan was set. Dangerous, yes. But it relied on the one thing Crowley didn’t believe they had.

Allies.

“They think I’m helpless,” Clara said, fingers tightening around resolve. “They think you’re a savage. We use that.”

Rowan kissed her palm, rough lips against calloused skin. “Ride fast, Clara Whitlock.”

At eight-thirty, Clara’s cutter crested the hill overlooking Juniper Ridge. Smoke curled from chimneys, but tension hung over the street. Sheriff Mercer and two deputies stood on the bank porch, rifles in arms, drinking coffee like men waiting for a show.

Clara lowered her hood, made her shoulders slump, and drove into town looking small, defeated. People stepped out to stare. They saw soot on her dress. They saw exhaustion. They mistook survival for surrender.

Inside the general store, the air stank of gossip. Clara walked to the counter where Mr. Baxter stood, an older man with kind eyes who had slipped her sugar when she couldn’t pay.

“Clara,” he said softly. “I heard about the barn. I’m sorry.”

“I need to send a telegram,” Clara said loud enough for the room to hear. “To my cousin in St. Louis. I’m selling the homestead to Mayor Crowley. I need a ticket out.”

A collective sigh moved through the store. Relief, not for Clara, but for the town’s appetite for drama being satisfied.

Baxter slid paper across the counter. Clara leaned in as if to write, but instead she scribbled three words and shielded them with her body.

HELP ME. PLEASE.

Then she slid one of Rowan’s gold coins under her palm.

Baxter’s eyes flicked to the coin, then to her face. He saw terror. He saw determination. He glanced out the window at Sheriff Mercer’s men laughing.

Baxter swallowed. Covered the coin. “I’ll send it right away.”

Clara whispered, “Tell them I’m saying goodbye at the church at noon. I want everyone there.”

She left.

Word spread like wildfire: the widow was leaving, goodbye at noon. Crowley heard and smiled like a man watching a trap finally close.

At eleven-forty-five, the town square was packed. People gathered because they loved endings as long as they didn’t have to live the middle. Crowley stood on the bank steps, looking benevolent, deed in hand.

Then the church bells began to ring.

Not a hymn. Not a funeral toll.

An alarm.

“Fire!” someone shouted. “Fire at the livery!”

Smoke billowed near the mayor’s own stables.

“My horses!” Crowley screamed, dropping his brandy glass. He turned to Sheriff Mercer. “Get the men! Go!”

The sheriff hesitated, eyes darting between bank and smoke.

“Go!” Crowley roared.

Lawmen ran. The crowd surged after them, eager for excitement. In moments, the street in front of the bank cleared.

And that was when Rowan Kincaid rode in.

Not in a cutter. On a stolen horse, bareback, galloping down Main Street like a storm given a spine. He did not hide his face. He did not sneak.

He wanted Crowley’s fear.

Crowley stood alone on the bank steps, fumbling for the pistol inside his coat.

Clara stepped from the alley beside the bank, shotgun leveled.

“Don’t,” she said, voice cold as the winter wind.

Crowley froze, eyes widening as he realized the widow he tried to crush was not bending. She was aiming.

Rowan slid off the horse, injured leg holding under pure will, and kicked the bank doors open.

“We’re here to make a deposit,” he bellowed.

He slammed a heavy leather sack onto the teller’s counter. It burst open, spilling gold dust and jagged nuggets across the ledger like the earth itself had decided to testify.

“Five hundred to clear the Whitlock mortgage,” Rowan growled. “And five hundred more to register a mining claim on North Fork Ridge in the name of Clara Whitlock.”

The teller, Mr. Abernathy, stared like a man watching his understanding of the world crack.

Crowley lunged inside, voice shrill with panic. “It’s stolen! He robbed a stagecoach! We don’t accept raw ore! We need United States tender!”

Clara stepped forward and snapped the shotgun closed with a sharp clack that echoed.

“The bank charter,” she said, calm and deadly, “Article Four, Section Two. In the absence of specie, the bank shall accept raw gold or land deeds at current market value.”

She looked at Abernathy. “Weigh it.”

Abernathy’s hands shook as he reached for brass scales. He scooped dust, added weights, watched the balance tip.

“It’s… it’s over twelve hundred dollars by current assay,” he whispered.

“Stamp the deed,” Clara said. “Paid in full.”

Crowley snarled and lunged for the counter.

Rowan moved faster than a wounded man should. He grabbed Crowley by the lapels and slammed him into the iron bars of the teller’s cage. Metal rang like a church bell.

“You tried to steal her land,” Rowan hissed. “You tried to burn her out. You sent killers to her door. You are done giving orders.”

Crowley screamed toward the open door. “Sheriff!”

Boots pounded on the boardwalk. Sheriff Mercer burst in, deputies behind him, rifles raised.

“Drop him, Kincaid!” Mercer shouted, Winchester leveled at Rowan’s back.

Clara stepped between the rifle and Rowan, her body a human shield.

“If you shoot him,” she said, voice trembling but loud, “you’ll have to shoot me too.”

Mercer’s jaw clenched. “Clara, move.”

A voice from the doorway cut through tension like a blade.

“He’s a hero.”

Mr. Baxter stood there, blacksmith beside him with a hammer, schoolteacher behind them, baker, ranch hands, and even women who had giggled earlier now looking uncertain, confronted by the shape of their own cruelty.

“We saw the fire,” Baxter said. “We saw who started it. It wasn’t Kincaid. It was Crowley’s men.”

“And we heard about the foreclosure clause,” the blacksmith added. “Throwing a widow out a day before Christmas. That ain’t law. That’s cruelty.”

Sheriff Mercer looked at the crowd, then at Crowley, then at the gold, then at Clara’s face.

Slowly, he lowered his rifle.

“The town pays my salary,” Mercer said, voice tired, “and it looks to me like a private transaction has been concluded.”

Crowley’s power evaporated in real time. He stumbled backward, eyes darting like a cornered rat.

Abernathy brought the stamp down.

PAID IN FULL.

The sound was small, but it was the sound of a future being reclaimed.

Clara took the stamped paper, fingers brushing wet ink like it might vanish if she blinked.

Rowan swayed.

The rage that had held him upright drained away, leaving blood loss behind.

“Rowan!” Clara caught him as he buckled.

“I’m all right,” he mumbled, but his eyes were losing focus.

Hands reached out. Baxter. The blacksmith. Even people who’d avoided Clara’s gaze yesterday now moved to help. They carried Rowan out not as a criminal, but as a man who had finally forced Juniper Ridge to look at itself.

The ride home blurred into pain and relief. The doctor stitched Rowan’s wound and muttered about stubborn constitutions and miracles. Night fell, and the farmhouse that had felt haunted by Samuel’s absence now held a different kind of presence, something living.

Clara sat beside Rowan with a mug of broth, watching his chest rise and fall, terrified that if she looked away he would vanish like smoke.

His eyes opened.

“You’re still here,” he rasped.

“Where else would I be?” Clara said, and her voice broke because the answer contained everything she’d lost and everything she might still have.

Rowan tried to sit up, wincing. “I need to go. Soon as I can stand.”

Clara froze. “Go where?”

“Back to the high country,” Rowan said, staring into the fire like it held judgment. “I did what I came to do. You’re safe. You’ve got your land. You don’t need a broken trapper cluttering up your life.”

“Is that what you think you are?” Clara asked, anger rising like heat. “Clutter?”

Rowan’s mouth tightened. “I’m a wild thing, Clara. I don’t know how to sit at tables. Don’t know how to talk at socials. I kill things for a living. Today was a fight. I’m good at fights. Tomorrow is… living. And I don’t know if I fit inside a house with curtains and a Bible.”

He looked at her then, expression raw. “Folks will talk. They’ll say you took in a stray dog. You deserve a gentleman.”

Clara set the broth down with a sharp clink, the sound of decision.

“I had a gentleman,” she said softly. “Samuel was a gentleman. He was good. And he’s gone.”

She leaned closer, taking Rowan’s rough hands in hers.

“Yesterday I stood on that stage and begged for someone to see me. Not my basket. Me. And the gentlemen of this town looked at their boots and let me drown.”

Her thumbs brushed his scarred knuckles.

“Only one man looked up,” she whispered. “Only one man walked through a blizzard and paid a fortune for stale biscuits just to give a widow her dignity back.”

Clara’s eyes filled, but her voice held.

“I don’t need silk ties,” she said. “I need a man who chops wood when I’m tired. I need a man who stands between me and wolves. I need you.”

Rowan’s breath hitched like he’d been shot again, but this wound was different. It was the kind that healed by being tended.

Clara rested her forehead against his. “Don’t go back to the cold. Stay. Be warm.”

For a long moment, Rowan didn’t move. Then he lifted one hand and cupped her face, thumb wiping away a tear like it mattered.

“I ain’t got much to offer,” he whispered. “Just a rifle, a bad leg, and a heart that doesn’t know what to do with itself.”

“A heart,” Clara said, smiling through tears, “is the only thing I’m asking for.”

Rowan’s eyes softened, and he leaned in.

The kiss wasn’t desperate or fueled by adrenaline. It was slow, full of the quiet promise that tomorrow could be lived, not just survived.

Outside, snow fell again, soft enough to look gentle, covering the scars of fire and footprints and attempted cruelty. Inside, the hearth crackled, and warmth gathered like something holy.

Three days later, they married in the parlor because the roads were snowed in and life didn’t wait for perfection. Mr. Baxter read from the Good Book, Sheriff Mercer signed as witness, and the blacksmith stood awkwardly, hammer left outside as if to prove he came in peace. Rowan wore his cleanest flannel and boots polished until they shone. Clara wore her gray dress, but she pinned holly at her collar, bright red like a stubborn heartbeat.

In spring, they didn’t sell the land.

They worked it.

They filed the claim, mined the ridge, and pulled enough gold from the earth to build a barn that didn’t just replace what was burned, but surpassed it: painted bright red, loft smelling of sweet hay, doors that swung without sagging.

But they built something else, too, because gold was not the lesson. Gold was the tool.

They built a long table on the porch where anyone passing through, hungry or cold, could sit and eat without being auctioned or judged. Rowan, who had lived years in solitude, learned the rhythm of shared meals. Clara, who had been watched in her suffering, learned the quiet power of being the one who offered warmth.

Mayor Crowley left Juniper Ridge within a month, slinking out like a man escaping his own reflection. His reputation died before he did. He spent the rest of his years chasing places where no one knew his name, proving that a man who measures worth only in ownership is always starving, no matter how much he steals.

As for Juniper Ridge, it changed slowly, like a thaw. People didn’t become saints overnight. They still gossiped. They still flinched at difference. But they remembered what happened the day a widow refused to disappear and a mountain man paid five dollars for her dignity.

And every year, on the anniversary of the Christmas box social, Rowan would clear that porch table and take out a small velvet pouch from the mantel. He’d pour five heavy gold coins into his palm, the same kind that had once clattered onto a table and frightened a town into silence.

He’d look at Clara, her hair now threaded with silver, her eyes still sharp, her hands still strong.

“Nobody bid on that basket,” he’d say, voice warm with awe that never faded.

Clara would cover his hand with hers and reply, “Nobody but the one who mattered.”

And in that simple exchange lived the truth Juniper Ridge learned the hard way: the value of a person is not decided by a room’s silence. Sometimes it’s decided by the one brave soul who refuses to stay quiet.