Ola L. Mize was captured during the Korean War, beaten for information he refused to give, and turned a prison camp into a battlefield by quietly sabotaging his captors instead of saving himself.

In November 1950, Private First Class Ola L. Mize was fighting with the U.S. Army near the Chongchon River when Chinese forces overran his unit. The retreat collapsed into chaos. Ammunition ran low. Communications failed. Mize was wounded, surrounded, and taken prisoner. Survival, at that point, meant compliance.

He chose defiance.

The Chinese quickly realized Mize was not an ordinary captive. He refused to cooperate during interrogations, even as beatings escalated. Guards demanded information about American positions and movements. Mize gave them nothing. When threats failed, punishment followed. He absorbed it without changing his answer.

Then he did something far more dangerous.

Inside the prisoner of war camp, Mize began organizing resistance. He sabotaged guard routines, disrupted roll calls, and created confusion that allowed other prisoners to evade abuse and secure food. At night, he attacked guards with stolen weapons, k!LLing several captors in close combat. Each act increased the certainty that he would be ex3cuted if discovered. He did not stop.

The decisive moment came when the camp descended into disorder.

As Chinese control weakened, Mize led prisoners in coordinated actions that overwhelmed guards and created opportunities for escape and survival. His actions directly saved the lives of fellow prisoners who were too weak, injured, or targeted to endure further punishment. He did not wait for liberation. He created it in pieces.

By the time Allied forces regained the area, Ola L. Mize had k!LLed multiple enemy soldiers, survived repeated torture, and protected dozens of prisoners without rank, authority, or backup. He was still a private.

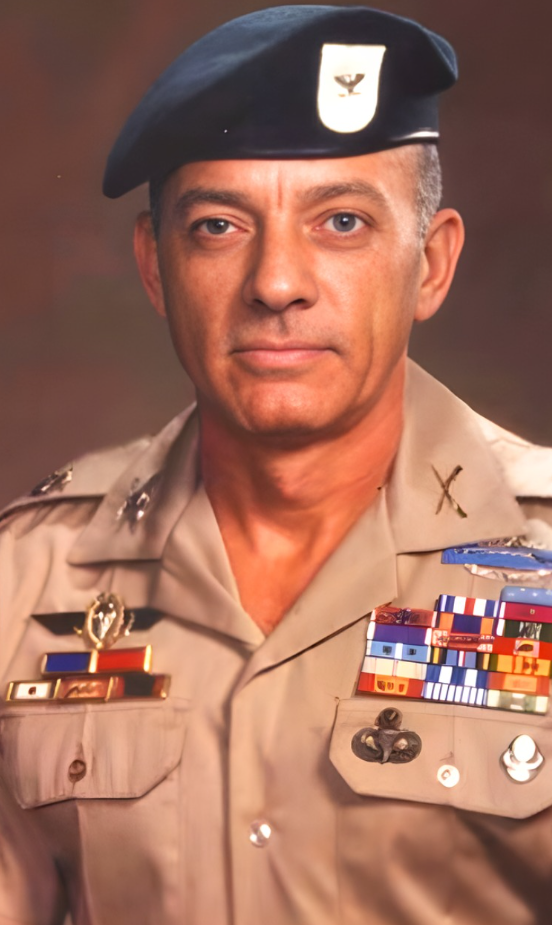

In 1951, President Harry S. Truman awarded Ola L. Mize the Medal of Honor.

The citation described “conspicuous gallantry” and “intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty.” What it could not fully express was the isolation of the choice. Mize could have endured quietly and likely survived the war. Instead, he accepted near certain death again and again to disrupt a system designed to break men slowly.

After the war, Mize returned to civilian life without fanfare. No career built on heroism. No public crusade. He worked, lived quietly, and carried memories few around him could understand. The violence did not end neatly. It simply stopped being visible.

Ola L. Mize did not fight for medals or recognition.

He fought because captivity did not excuse surrender.

Heroism is often imagined as a single explosive moment.

His was sustained, deliberate resistance in a place designed to erase it, proving that even stripped of freedom, a man can still decide who he is.