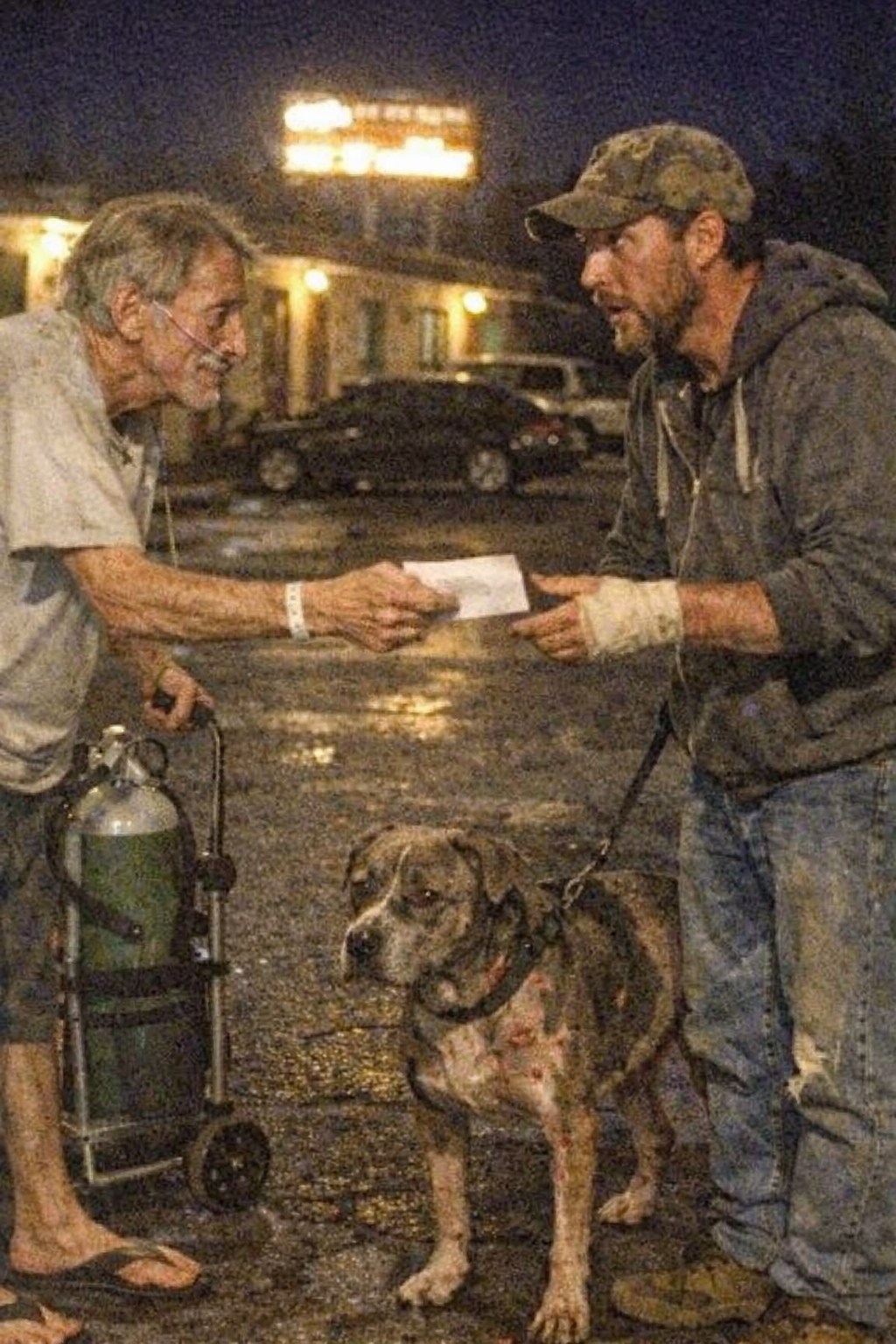

The night I watched a dying man hand his last treatment money to save a mangy, growling dog, I realized who America really forgets.

I work nights at the Maple Star Motel off Exit 19, the kind of place where the sign flickers and the ice machine screams louder than the highway. The TV in the lobby is always tuned to some panel show—people in crisp suits arguing about “values” and “responsibility” while my guests pay in crumpled cash and count quarters twice.

That’s where I first saw him: the vet and the dog.

He checked in just before midnight. Tall, mid-forties, sunken eyes, beard scruff like steel wool. He carried everything he owned in one duffel and one leash. The leash wasn’t much. The dog at the end of it was even less.

She looked like something the world had already decided to throw away. Patchy fur, raw red skin where mange had eaten through, ribs like a broken xylophone. She smelled like infection and rainwater. When anyone walked too close, she’d curl her lips back and let out this low, steady growl that vibrated in the tiles.

“Dogs aren’t allowed,” my manager, Mrs. Clarke, reminded me after he walked away. “Last thing we need is some liability lawsuit. Tell him to put it in a shelter.”

“It” never had a name when they talked about her.

He came up to the desk the next morning, hat in hand. “I’ll pay the pet fee,” he said. “She just needs a few weeks till I find something steady.”

“You got work lined up?” I asked.

He shrugged one shoulder. “Day labor. Maybe security, if they don’t mind the noise in my head.”

That’s when I saw the faded flag patch on his backpack, the unit logo on his cap, the hospital bracelet still on his wrist. He didn’t say the word “veteran.” He didn’t have to.

Two doors down from him, in 108, we had Mr. Harris.

Mr. Harris was the kind of man who still said “ma’am” even when he had every reason not to respect anyone anymore. Late sixties, skin yellowed at the edges, a cough that sounded like it was ripping something loose every time. He rolled an oxygen tank behind him like a reluctant child.

He checked in with a stack of papers and a shoebox full of pill bottles. He laid the papers on my desk once when his hands were shaking too much to hold them. Even upside down, I could read words like “ineligible,” “not covered,” and “out-of-pocket estimate.”

“You’d think after forty years on the line, somebody would pick up the tab,” he joked, but his eyes smudged at the corners when he said it.

The first time those two men and that dog really collided was three days later, out in the parking lot.

I was on my lunch break, sitting on the curb with a vending machine sandwich, when I heard the growl. Not the warning growl I’d gotten used to, but something panicked, wild. I rounded the corner and saw the dog twisting in her own skin, scratching so hard she was bleeding again. The vet was kneeling beside her, trying to hold her still.

“Easy, Lucky,” he murmured. I realized then she did have a name. “I know it itches, girl. I’m trying.”

He had a bottle of generic cream from the dollar store, nearly empty. His forearms were covered in old scars and new scratch marks. There was desperation in the way he tried to rub the medicine on without getting bitten.

“You’re going to get yourself torn up,” a voice rasped.

Mr. Harris shuffled out of the shadows between the parked trucks, oxygen line dragging, flip-flops slapping the concrete. He lowered himself onto an upside-down milk crate like each vertebra had to negotiate the move.

“She doesn’t like strangers,” the vet warned.

“Neither do I,” Mr. Harris said. “But here we are.”

He didn’t reach for the dog. He didn’t croon or baby-talk. He just set a small brown paper bag on the ground and nudged it closer with his foot. The smell of real food leaked out—chicken, rice, something warm. The dog’s nostrils flared.

“Try mixing this in with her kibble,” he said. “Gentler on the stomach. Vet down the road recommended it to my neighbor. Also…” He fished into his shirt pocket and pulled out a folded receipt and a white envelope. “This is from the pharmacy.”

The vet frowned. “I can’t—”

“It’s topical stuff for mites,” Mr. Harris cut in. “I told them it was for a friend’s dog. They gave me a discount.” He handed over the envelope. “Paid in cash. No one has to see any forms.”

The dog took a hesitant step forward, then another, drawn by the smell. She snapped at the vet’s hand once, out of habit more than hate. He held still. She stopped, confused, then lowered her head and began to eat from the bag, shaking.

I saw the red smear blooming on his palm. I saw the tremor in Mr. Harris’s fingers. For a second, all three of them looked like they might fall apart.

“You shouldn’t be spending money on us,” the vet said quietly. “You’ve got your own fight.”

Mr. Harris looked at the dog, then at the thin man in the army cap, and finally at the cracked parking lot stretching out to the freeway.

“Doc says there’s a new treatment we could try,” he said. “Might buy me six months if it works, might not. Costs more than this whole motel makes in a week.”

He shrugged, this slow, tired roll of his shoulders.

“I spent forty years believing the folks on TV when they said if you work hard and play by the rules, someone will catch you when you fall,” he said. “Turns out, the net’s got bigger holes than I thought.”

He nodded toward the dog, who was licking the last grain of rice from the bag, sores still angry but eyes softer.

“I can’t fix the holes,” he said. “But I can make sure one scruffy soldier and her human don’t fall straight through.”

Later that night, after the ambulance took Mr. Harris away for the last time, I found the motel ledger under the counter. Tucked inside was a receipt from the clinic down the road, payment in full for a “canine exam, treatments, vaccinations, registration.” On the signature line was Mr. Harris’s shaky handwriting.

There was also a note, in the same unruly scrawl:

Room paid for four more weeks. Dog stays with the soldier.

If anybody asks who approved it, tell them it was the man who didn’t have time to spend his miracle on himself.

The news channel in the lobby was still debating who “deserves help” and what “personal responsibility” really means. They didn’t mention Mr. Harris, or the vet in 112, or the mangy dog now snoring with her head on an old army jacket.

Out in the parking lot, under a flickering sign that promised “Low Weekly Rates” to no one in particular, a sick old man chose to use his last bit of leverage on earth to say, you matter to two creatures the world had already written off.

That’s when it hit me: maybe this country isn’t measured in speeches or slogans or perfect success stories. Maybe it’s measured in the tiny, quiet trades we make in broken places—the days we choose to bleed a little so somebody else, even a dog with mange, gets one more chance to heal.

And if that’s true, then the people we forget the fastest might be the ones holding up more of this country than we’ll ever see on any screen.